The following will spoil your enjoyment of One Piece and your “enjoyment” of X-Men Second Coming. You have been warned.

Superhero comic readers are a bloodthirsty lot. They often call for the death of characters, in the belief it somehow adds “realism” and makes stories “important”. They will then go on to complain that the deaths they get feel empty, because characters are always coming back to life.

These people have got it all wrong.

What causes the deaths to mean nothing is the fact that there are too many of them. A character’s death can’t be treated as an important event, when these “important events” seem timetabled. The reason Gwen Stacey or Captain Mar-Vell’s deaths are treated with such reverence is not because they’ve never been brought back to life, but because they happened at a time when they had a chance to stand out.

X-Force #26 and One Piece Chapter 573 both feature characters getting killed by a punch through the chest. Only one is effective.

Eichiro Oda’s One Piece is notable for how rarely it uses it death to wring out an emotional response from the reader. He doesn’t need to, his got the tools to do that with just having people raise their arms in the air or place a hat on a head. For the most part he’s reserved the death of sympathetic characters for origin stories told in flashback. That, combined with an early interview with Oda and some ludicrous near-death experiences characters went through during the Alabasta arc, gave readers the impression that people wouldn’t die in the ongoing story.

In Chapter 573 he proved them wrong. The past 50 or so chapters had involved the hero of One Piece, Monkey D. Luffy, attempting to rescue his adoptive brother, Portgas D. Ace from execution at the hands of the Marines. He succeeded in this attempt, only for Ace to be killed saving Luffy from Admiral Akainu, a particularly driven Marine with the power to turn into magma. Ace had actually only appeared a few chapters of the manga, but because this was the first death of a sympathetic character in the ongoing timeline of the book, not to mention the emotional investment the reader had with Luffy’s attempt to rescue Ace, it had a genuine impact on the readership. A readership that had been growing over the storyline, due the stakes involved.

X-Force #26 is chapter five of the current X-Men mega crossover event, Second Coming. It’s written by Craig Kyle and Chris Yost, two writers who have the opposite reputation to Eiichiro Oda when it comes to death. In the opening chapter we learn that during the last event they wrote, Necrosha, three X-Men died. By the time X-Force #26 rolls around, another X-Man has already died (Ariel, a little used character from Fallen Angels), a villain has been killed (the frequently dead Cameron Hodge) and so have many un-named goons. It’s a franchise that is up to its ears in death.

So when beloved, long time X-Man, Nightcrawler takes arm through the chest to save the “mutant messiah” Hope, rather than being an emotional moment, it’s just another death in a series that is soaked in it. Though, in the same way that the emotional investment you have in Luffy is also a factor in addition to the novelty of Ace’s death, there’s plenty of other factor’s hurting Nightcrawler’s death scene too.

There’s no emotional investment in either Hope or Nightcrawler, let alone between them. Unless you’ve been reading Cable, Hope is just a MacGuffin in this story. Not even a good MacGuffin, we’re told she’s important, but never actually why she is. And Nightcrawler has barely featured in what is ostensibly his book, Uncanny X-Men, let alone X-Force or Cable. Plus, for long time fans like myself, it’s been ages since he’s been written as the Nightcrawler we actually liked, as writer after writer seemed to just focus on the catholicism aspect of his character, rather than the fun loving guy Claremont wrote, or the most sensible man in the room of Alan Davis and Warren Ellis’ Excalibur. But that’s really beside the point, they’ve spent two years building up to this event and they kill off two characters who had next to nothing to do with the build. It’s fictional collateral damage.

Then there’s the matter of there being no emotional investment in the villains. The villains of Second Coming are the dregs of 90s X-Men comics, losers like Graydon Creed and Bastion. They’re a clumsy metaphor that doesn’t make sense any longer, in the same way the reduction in the number of mutants completely missed the point too.

In One Piece, even Akainu, whose appearances are dwarfed by Second Coming’s band of wastrels, garners more of an emotional response, because he’s terrifyingly easier to understand. He’s the soldier who has abandoned personal choice in order to simply follow the rule of law. He’s not pantomime villain evil, he’s a man so devoted to an implacable set of values that he can’t be argued with. On his own that might be an overly simplistic villain, but he’s set in contrast with the behaviour of the other Admirals, and the other Marines as a whole.

There isn’t the same distinction between Second Coming’s villains, who might as well be chanting “WE HATE MUTANTS AND WE HATE MUTANTS! WE HATE MUTANTS AND WE HATE MUTANTS! WE HATE MUTANTS AND WE HATE MUTANTS! WE ARE THE MUTANT HATERS!” all through the book. Reaction to Ace’s death was anger at the character of Akainu, reaction to Nightcrawler’s death is either indifference or anger at the writers/editorial.

The frequency with which those are the reactions to death in superhero comics is a good sign that there’s something deeply wrong with how death is handled in superhero comics.

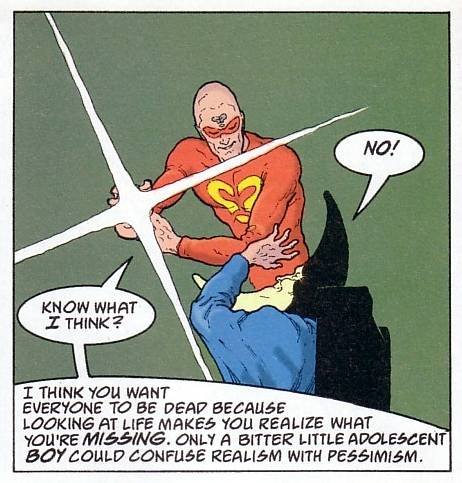

To conclude, we need Flex Mentallo back in print so The Hoaxer can tell these superhero writers and readers how it is:

Ace’s death fucked my brain. I was living in a happy, shiny One Piece dimension, where Oda never kills anyone and I was ok with it.

So my initial reaction was “whuh? Hbpbpbbbbl.”

That picture is awesome and very appropriate. I am not very well-read in superhero comics, but that art seems naggingly familiar. Do you know who the artist is?

It’s Mike Choi