Before my computer died I had a wonderfully long post on the Violence Jack manga prepared. However that is GONE. And so you will instead be suffering an insufferably long series of posts on each chapter of the manga.

But first a couple of disclaimers:

I’m reading the Japanese “Complete Violence Jack” collections. There are two problems with this. The first, most obvious one, is that I can’t read Japanese. What little knowledge I had is long rusted, however if this was a big problem, I wouldn’t be doing this. Nagai’s cartooning skill, especially in the 70s chapters, is strong enough to get over that speed bump. It’s more of a problem in the 80s chapters where… well you’ll see…

Secondly, while the “Complete Violence Jack” is relatively complete, collecting the 70s shonen incarnation and the 80s seinen incarnations, it doesn’t collect the chapters in chronological order. Which makes things fairly confusing in the 80s chapters. Not so much from a continuity point of view, but from a tonal perspective. While the 70s chapters are fairly similar in tone, the 80s version changes over time, and when they are published out of order it’s rather jarring.

—

Violence Jack has something of a reputation in the UK, due to the Manga Video release of the OAVs in the 90s, their subsequent cutting by the BBFC and constant reassuring by Helen McCarthy that the manga is much worse. And to be fair, it is. Sometimes. But not as often you’d think.

In fact, Violence Jack started in the pages of Weekly Shonen Magazine in 1973, hot on the heels of Nagai’s Devilman. As that series had ended with an apocalypse, Violence Jack opens with one. But unlike Devilman’s man/devil-made end, Violence Jack’s is a natural disaster – The Great Kanto Earthquake. After a brief appearance from Jack, we see a general summary of what caused Japan to turn into this wasteland, before meeting the actual main character of the series (at least for now), Ryou Takuma.

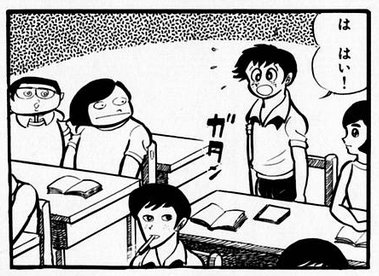

Ryou is a young boy living in Tokyo and he is, essentially, the reader. Like a lot of early Nagai heroes, he’s a short, bullied kid who finds it within him to be a hero. We see him going about his life, dealing with the first few tremors of the disaster to come. Then during an average school day, the world ends.

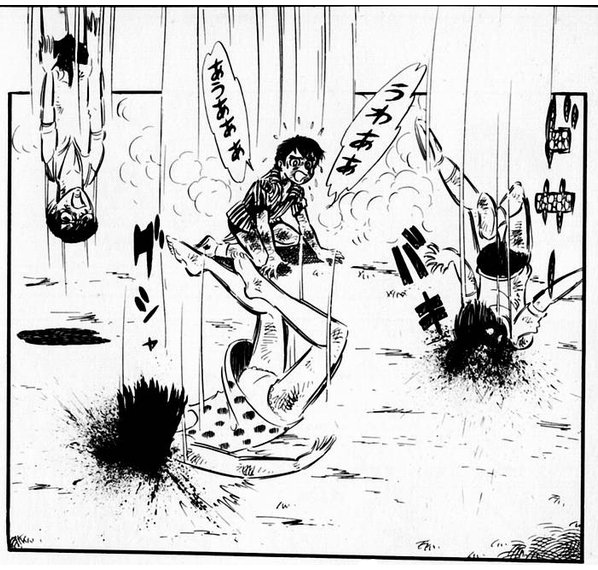

And keeps on ending. Almost all the 250 pages of the first story is given over to Ryou going from his peaceful everyday existence, through hell on earth, everyone he knew dying, until he emerges as the leader of a band of children living in the slums. Jack himself appears on little more than 11 pages of this first tale, interacting with no-one.

Nagai will come back to this approach later on in the series, giving future characters similar flashbacks to the pre-Earthquake time, but outside of a couple of flashback specific chapters in the 80s, this is probably the most extensive use he makes of it. Given the timing of the series release, I do wonder if Kazuo Umezu’s Drifting Classroom was an influence, alongside late 60s/early 70s apocalypse pop culture like Omega Man.

As well as being relatively lacking its title character, there’s another trademark element of Violence Jack that doesn’t come into play in this first story. It’s one that doesn’t get mentioned enough in discussion of the series and I’ll get it when if first raises it’s head in the next story – Kanto Slums Chapter.